Chapter

1

May, 1783

“Wretches so disgraced with infamy and

crimes…”

—Albany County resolution

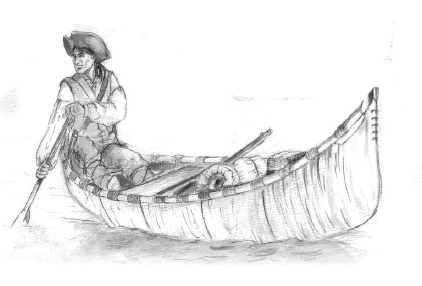

A birch canoe glides along the lakeward side of a curiously narrow

strip of beach, the man in the stern turning to look through the

waving grass and stunted oaks.

He’s lithe and dark with a seasoned face

and deep-set eyes. The hair, under a broad-brimmed hat, is long

and tied back in a queue.

Small waves beat the shore where finch and sparrow

chatter. The man stays the paddle to gaze beyond the beach.

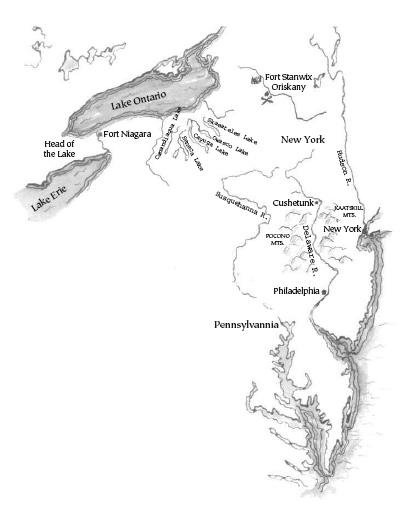

One of the British officers at the fort spoke

of this sprawling harbour at the head of the lake, a place the

Indians call Wequatetong.

But what he sees beyond this long beach is more

like another lake than a harbour.

For three days he’s been coasting west

from Fort Niagara, exploring the mouths of streams and creeks.

The war that ranged up and down the thirteen

colonies for eight years, is effectively over and provincial troops

and volunteers, like Robert Land, who have no further military

purpose, are striking out to explore the land of their exile.

Exile indeed, all have heard accounts of Loyalist

soldiers, bold enough, or foolish enough, to return to homes they’d

left during the war, only to be whipped and driven away.

The bitter truth was, Americans like Land, who

backed the losing side during the revolution, had been banished

and could never go home.

Slowly, new lands west of Niagara River were

being opened and refugees of that war were looking for new homes.

One inlet, a 20-mile paddle from Niagara had been promising. Some

of Butler’s men had already claimed land there but it was

just a pond compared to this bay. Sheltered yet large enough to

accom modate whole fleets.

A strand of grey sand, matted over with waist-high

grass and dotted with groves of squat oaks separates the bay from

the lake. Beyond the bay lies the low stony ridge that parallels

the lake all the way from Niagara. The only feature on an otherwise

flat expanse of forest.

Land finds the natural outflow that drains the bay,

shallow, languid and easily crossed. Drawing up his paddle he

looks to where the bay shallows out in swale and marshland. Beyond

that, the land rises in two rolling steps to the rocky spine.

Unlike the steep tracts that hem the Delaware this is level land,

good for crops.

Crossing the bay, he can see the dark forms

of salmon below. Easing his canoe through swatches of wild rice,

he works down a narrowing inlet overhung with willows. Three deer,

drinking at the water’s edge lift their heads. On land,

clouds of pigeons dip and wheel above the forest.

At the end of the inlet Land ties off. Shouldering

his musket and hunting bag, he steps through the scrub into the

cool darkness of the forest.

The war’s over but he still moves with

the natural wariness of a fugitive.

Starved of light, there is little undergrowth

on the forest floor and he moves easily through ferns and white

lilies. Beneath the luminous canopy grander than any church Land

saw in New York, the air is damp, heavy with the earthy smell

of leaf mould. The forest hums with insect and bird song.

He is struck by the familiarity of this forest,

so similar to the great timber stands along the Delaware he helped

harvest and raft down river to Philadelphia. With the eye of a

woodturner he surveys walnut and basswood and sees sturdy furniture.

But mostly he sees a vast spread of bottom land a hundred times

the size of the river flats he’s left behind.

The terrain is not flat but rolls and rises

gently. Several creeks have carved ravines that snake down to

the bay. Occasionally there are open grasslands, perhaps the result

of a fire break or an ancient beaver meadow.

Topping a small rise in one of these meadows, Land stops to rest

and watch a large rattlesnake slither away. He cuts a twist of

dark tobacco, tucks it into a stained clay pipe and tops it with

a knot of flax. Steel and flint collide in a shower of sparks,

he draws deeply, pulling fire into the bowl.

Surveying a nearby grove of beech trees, Land

rubs a pinch of the rich black earth between his thumb and forefinger

and nods. Corn, squash, beans and maybe even a little wheat on

the higher ground.

There is promise in this new land, already in

his mind he can see a cabin and corn crib, perhaps a stable…

So much to gain…

But so much lost…

The pipe slips from his hand and a jumble of

images flash with the intensity of lightning—each full of

sharp pain and sorrow.

His youngest son’s dirty grey burial shroud—Dear

Will, you knew nothing but war and want—the charred remains

of the Delaware homestead— 15 years of labour, torched in

fear and resentment. The oldest son, hanged and humiliated like

a dog—Poor John, the price you paid for being first born.

The contorted faces of enemies who once were friends and neighbours—Robert

Land, this court martial sentences you to death for treason. The

lead musket ball that flattened him with the force of a falling

tree, the trusting face of his mountain guide, Morden—flee

Land, flee!—dead at the end of a Rebel rope rightly meant

for him. The brave, trembling smile Phoebe had worn the last time

he left his family —Go well Robert, and return to us soon…

Dizzy and sweating in a sun that has suddenly

become unbearably hot and threatening, Land lurches to sprawl

facedown in the shade of the beech grove and draw coolness from

the dark earth.

So much blood, so much pain. So many widows,

so many orphans. In his mind he can hear, rising and falling,

the keening wail of the Iroquois death rites. Slowly the pounding

in his head begins to subside, his breathing gradually eases and

the fevered images begin to fade.

To rest a moment in the cool darkness of this

wilderness wood so far from what used to be home, so far from

family. And to wonder if life can be restored after so many destructive

years…the years of rage and ruin when all the world turned

upside down…

Copyright © James E. Elliott 2009. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be stored in a

retrieval system, transmitted or reproduced in any form or by

any means, photocopying, electronic or mechanical, without written

permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright

Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence,

visit <www.accesscopyright.ca> or call 1-800-893-5777.

|